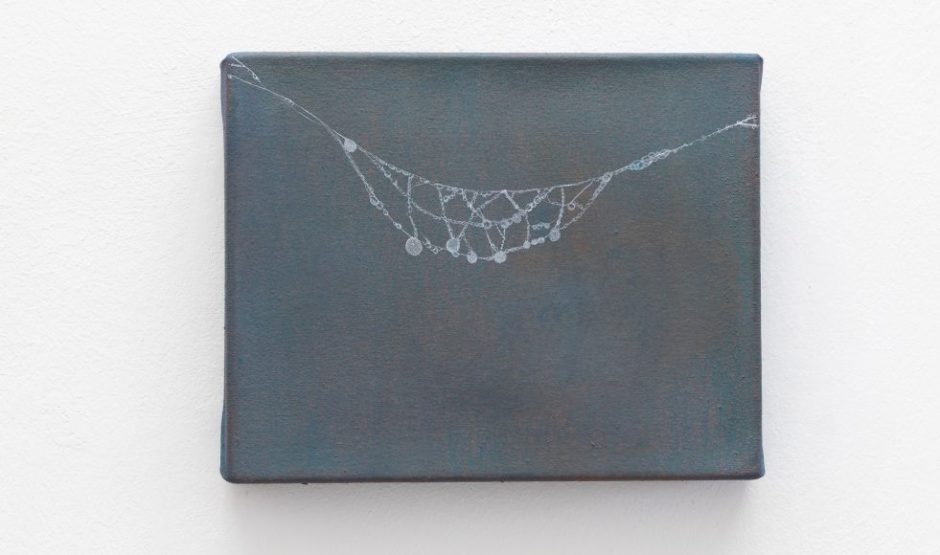

Is an article that has been useful to think about my experimental drawing intervention. How do we access improvisation, and can such a thing as a truly free experience or drawing exist, or is every drawing and moment tied to other lines and other experiences?

Taking a Lone For a Walk starts off with a defining the difference between “connecting” and “active” lines, this can also be interpreted as compositional lines and improvisatory lines.

“… ‘connecting lines’ which look like broken segments, each one joining a point and the next one. Active lines are traced by wayfaring, which involves creating a path where there is none, along the travelling itself, as Machado has celebrated in his poetry:

As you walk, you make your own road,

and when you look back

you see the path

you will never travel again.

Traveler, there is no road;

only a ship’s wake on the sea.

(Machado and Berg 2003: 55)

By wayfaring, the traveller goes on in ways that are minutely responsive and attentive to the changing surroundings and to her life history.” 1

This link between drawing and walking feels very apt and neatly links the often used ‘taking a line for a walk’ idea around exploratory drawing. It is also a nice ways of thinking about how the mind works when we are consciously or unconsciously choosing where we take the line in our drawing. Nemirovsky and Dibley set a key part of ideology out from the start: they see the moment of making not as separate but as intrinsically tethered to the life experiences of the maker. I can only agree with this, we are not goldfish, each lived experience we have informs who we are, just as each line that we make in a painting or a drawing is informed by, holds the possibilities of each and every line we have made before.

It is interesting for me to think about how our own tacit knowledge and experiences of life and of making feeds into the act of drawing line, even if the aim is to let go and to let our mind and the line we make, wander. This also tickles the edges of one of my own concerns about this way of working: does improvisation or a lowering of control tap into a way of making that is more personal, more level or does it merely widen the gap between those who have had the time/learning/education/privilege to investigate their work and themselves. Is a student in a more comfortable life more able to easily access this way of making, given that is can be seen as having no end product or verifiable outcome?

The following quote is an account of a street encounter between Ricardo Nemirovsky and the artist and teacher Steven Lacy:

“I took out my pocket tape recorder and asked him to describe in fifteen seconds the difference between composition and improvisation. He answered: ‘In fifteen seconds the difference between composition and improvisation is that in composition you have all the time you want to decide what to say in fifteen seconds, while in improvisation you have fifteen seconds.” 2

Is a fun definition of the difference between composing and improvising. In this way, composition can be read as a play between performance and editing, a way of making that flows in two different types of time and two differing types of connectivity or movement. When composing an image, there are moments of ‘making’ or engagement purely between the maker and the material, though perhaps I would argue that even in this material connection, the maker is working with pre-conceived ideas. In improvisations there is only one time of time flow, and that is the present moment of making.

“Like wayfaring, improvising is a temporal practice open to the unanticipated and to the ongoing engagement with others, materials and instruments.” 3

I like this quote as well and the notion that improvised drawing. In my experience of making improvised drawings as a practitioner and listening to and watching students make these drawings, it is a way of making work that is of the present moment, of the now and is connected to the conditions around you. This feels like a way of working that keeps things open and allows for a more direct access to the play between maker and materials.

“Improvisation is neither chance nor a product of intelligent design, but the pre-eminent mode of live performance across all forms of life. Improvising entails openness to a quasi-autonomous play of forces, desires, inhibitions, memories, as well as of affects traversing materials, instruments and places” 4

I agree with this, that line drawing and improvisation are an expression of an individuals journey, a journey that is both inner and also informed by our experiences and out knowledge of the materials we are using. If we have spent a number of years making, drawing and learning about these things, the line we are making will be different to if we did not have these experiences.

“A lot of improvisors find improvisation worthwhile because of the possibilities. Things that can happen but perhaps rarely do. One of those things is that you are ‘taken out of yourself’. You can do something you didn’t realise you were capable of. Or you don’t appear to be fully responsible for what you are doing.” 5

The openness to improvise, to play is one of the key reasons I am want my students to learn how to look and think for themselves. We each have our own individual experiences, if these connections are allowed to come through, then they will be present in something even as simple as a line drawing. For me, this way of thinking lowering on the focus of our own technical control on what we make, opens up a space for a connection and play with the materials we are using which makes space for surprising things to emerge. Surely it is more invigorating to work with something that can bend, shift and move in ways that we have not pre-determined? After all, the journeys and connections we make in life is not formed in a straight line.

References

- Nemirovsky, Ricardo and Dibley, Tam (2021), ‘“Taking a line for a walk”: On improvisatory drawing’, Drawing: Research, Theory, Practice, 6:2, pp. 253–71, https://doi.org/10.1386/drtp_00064_1, page 254

- Nemirovsky, Ricardo and Dibley, Tam (2021), ‘“Taking a line for a walk”: On improvisatory drawing’, Drawing: Research, Theory, Practice, 6:2, pp. 253–71, https://doi.org/10.1386/drtp_00064_1, page 255

- Nemirovsky, Ricardo and Dibley, Tam (2021), ‘“Taking a line for a walk”: On improvisatory drawing’, Drawing: Research, Theory, Practice, 6:2, pp. 253–71, https://doi.org/10.1386/drtp_00064_1, page 255

- Nemirovsky, Ricardo and Dibley, Tam (2021), ‘“Taking a line for a walk”: On improvisatory drawing’, Drawing: Research, Theory, Practice, 6:2, pp. 253–71, https://doi.org/10.1386/drtp_00064_1, page 264

- Nemirovsky, Ricardo and Dibley, Tam (2021), ‘“Taking a line for a walk”: On improvisatory drawing’, Drawing: Research, Theory, Practice, 6:2, pp. 253–71, https://doi.org/10.1386/drtp_00064_1, page 268